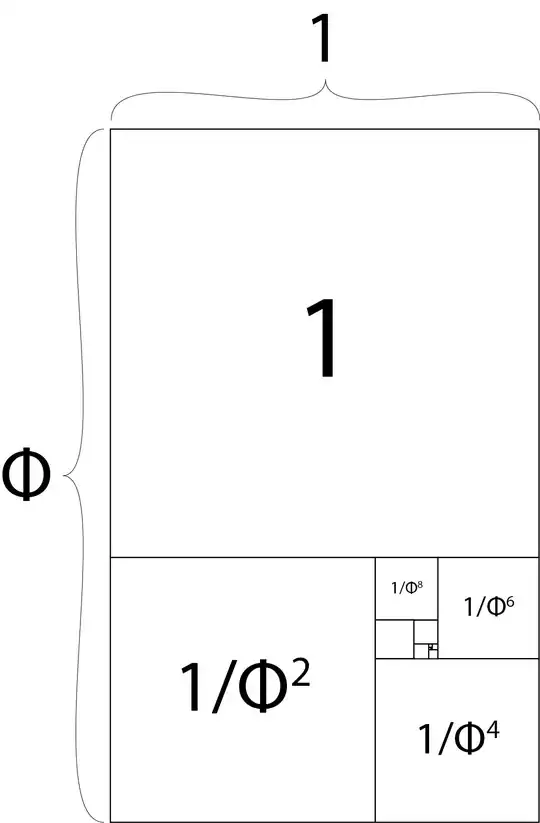

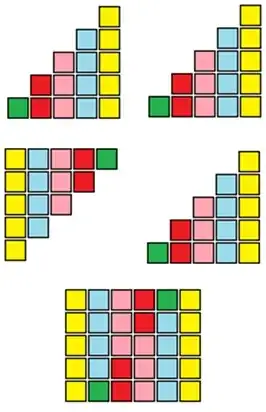

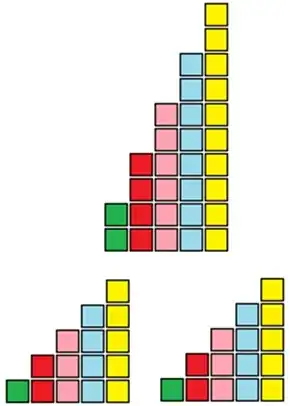

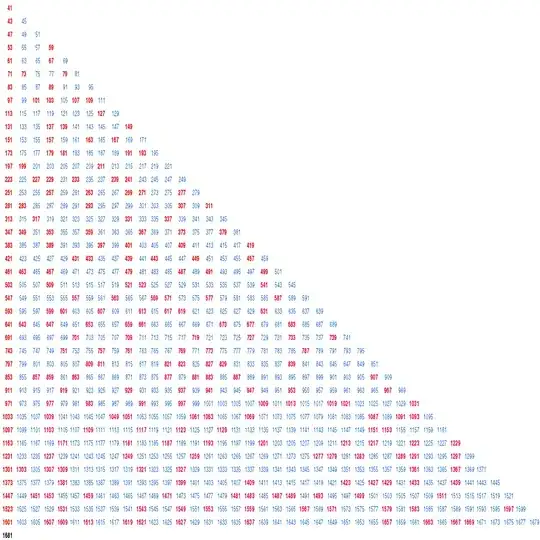

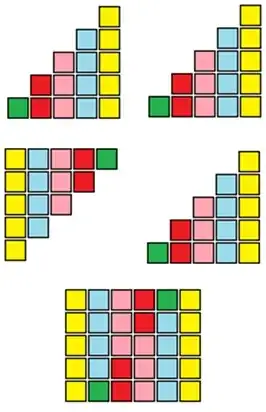

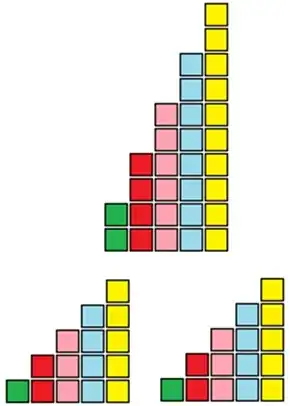

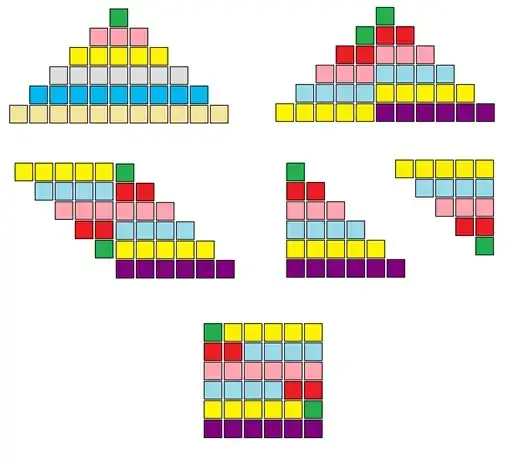

The classic examples of the first $n$ natural numbers, first $n$ even numbers, and first $n$ odd numbers are all nice introductions. Here are some pictures I created to help explain them using blocks:

Natural numbers:

Even numbers:

Odd numbers:

Similar to the binary example given earlier, here is one using ternary (base 3):

$$0.020202\ldots = \sum_{n = 1}^{\infty} \frac{2}{3^{2n}} = \sum_{n = 1}^{\infty} \frac{2}{9^n} = \frac{1}{4}$$

Though the question concerns the beginning Calculus level, those later in their mathematical learning may note that the line above indicates $1/4$ is in the Cantor set.

Since you asked for nonstandard: Rarely have I seen these problems asked in reverse. For example, Given a natural number $k$, what's an algorithm that could be used to determine if there is some $n$ such that the sum of $1, 2, \ldots, n$ gives $k$?

Does this approach work? Suppose you are given $666$. The sum of $1, 2, \ldots, n$ is $n(n+1)/2$, so we now ask whether there is an $n$ for which $2\cdot 666 = n(n+1)$. Taking the square root of the left side, we find $\sqrt{2\cdot 666} = 36.49657\ldots$, which suggests checking $n = 36$. (And it works!)

Similarly, suppose you are given $902$. Reasoning as above, we find $\sqrt{2\cdot 902} = 42.47352\ldots$, which suggests checking $n = 42$. (But no: $42(43)/2 = 903$. A narrow miss!)

One more: If you will allow for modifications similar to the $41 + \sum_{k=0}^{n}2k$ example, then consider:

$$23 + \sum_{k=0}^{n}6k$$

Observe that this can be re-written as $3n^2 + 3n + 23$, which is prime for $0 \leq n \leq 21$.

A nice follow-up problem is to prove that there cannot be a real-valued polynomial producing primes when evaluated at every natural number.